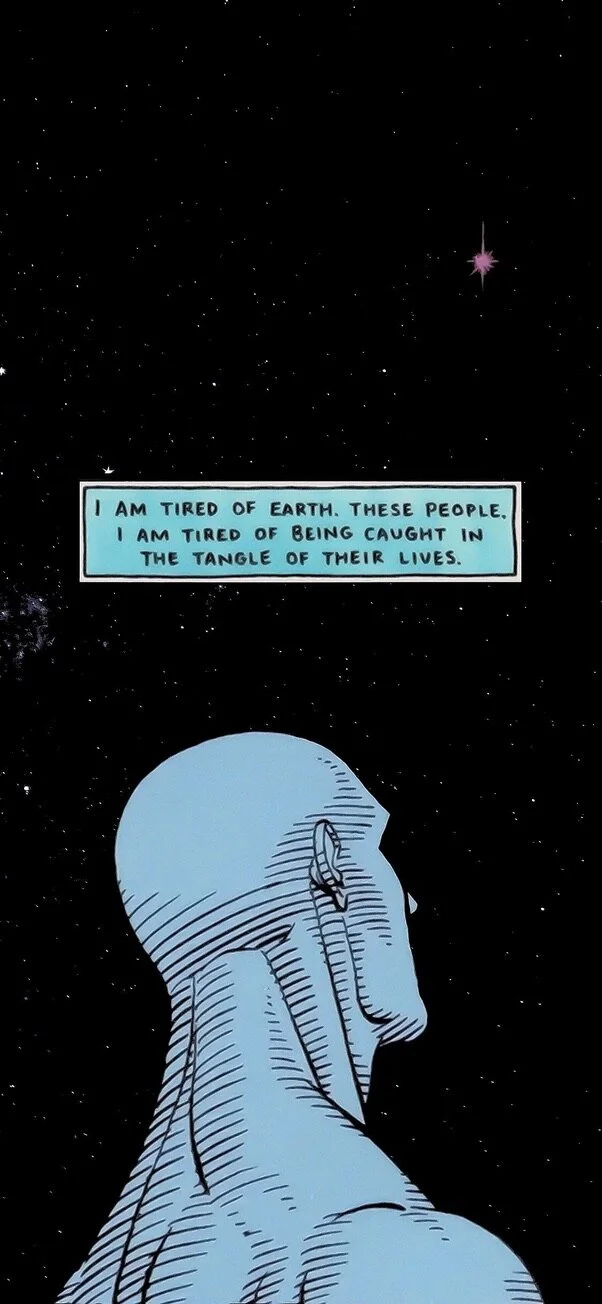

Dr. Manhattan, heroes and superheroes, identity, illusion, and (more) isolation.

Writing about comic books, in general, yesterday and briefly about Dr. Manhattan sent me down a bit of a rabbit hole of feelings. Not everything was about the good doctor, though I could probably ramble on and on about how I feel about him. I spent a lot of time thinking about Watchmen (the book) and how complex and how beautiful the story is. I know there is a lot that isn’t beautiful in it—the Comedian, Rorschach’s hardline leanings, the seedy alternate reality, amongst other things—but there is a lot of beauty in looking at these masked figures and seeing them as humans. Calling the characters heroes isn’t even really altogether fair to them and sets us, the Dear Readers, up for the rug to be pulled out from under us. I consulted the Good Ol’ Dictionary feature on my computer and the definition of hero came up as:

a person who is admired or idealized for courage, outstanding achievements, or noble qualities: a war hero. • the chief male character in a book, play, or movie, who is typically identified with good qualities, and with whom the reader is expected to sympathize: the hero of Kipling's story. • (in mythology and folklore) a person of superhuman qualities and often semidivine origin, in particular one whose exploits were the subject of ancient Greek myths.

With the second definition, I guess the ‘chief male character’ piece comes from there being a heroine noun, but in 2021 I think we can all agree the overarching term “hero” doesn’t necessarily need to be gendered, but that’s maybe another topic of conversation for another day. The final definition is intriguing with the noting of superhuman qualities and semi-divinity because while the definition of divine —“of, from, or like God or a god”—can carry a lot of ideas about goodness and whatnot, semi-divine is just like, you know, kind of divine, so who knows what watered-down version of divinity is existing within those characters. I think the first definition listed within ‘hero’ is the most intriguing, personally: “A person who is admired or idealized.” Like fame, the weight of herodom isn’t something one takes up and puts on oneself; rather, The People raise up one they decide is a hero or tear down one they decide is a villain. I think in The Dark Knight, it’s Aaron Eckhart who says, “You either die a hero or live long enough to become a villain.” Fascinating concept, especially when looking at the masked vigilantes in Watchmen or the next generation of heroes in Kingdom Come. What I think is so fascinating is the notion of a hero is so singular, so tied to one view of someone with no wiggle room; if you’re fighting villains and you’re someone like the Punisher, maybe you’re an anti-hero—you kill people, but it’s for the right reasons so it’s still kind of heroic. I mean, I don’t know. Is killing anyone under any circumstance heroic? Who knows. That, Dear Reader, is another another-conversation-for-another-day. So, in the context of Watchmen, you have these characters who are maybe, in the first little, bit presented as superheroes—not just heroes, but superheroes—because they present in all the ways we expect superheroes to present with masks, apparent superpowers (or at least beyond-average abilities), pseudonyms, and secret identities. The beauty of Alan Moore’s writing, however, is that these are normal people, or, at least, as normal as they can ever be.

Dr. Manhattan is maybe the most obvious person to gravitate to when it comes to trying to parse out a person from a hero. Dr. John Osterman was normal, by all accounts. Smart, sure, but I never saw him on the Tony Stark/Reed Richards/Victor von Doom/etc.-level where he’s a genius’ genius; of course, it’s very possible I missed something in my reading, but I just never saw Osterman as that Big Brain, so to speak. So, Osterman is just being Osterman when he becomes Manhattan and everything changes for him; his colleagues around the base see a body reforming in the air over the course of a week or something (I can’t remember—I don’t have my book in front of me to confirm the length of time and googling everything to make it pitch perfect feels too polished for me today), but we know that Dr. Manhattan doesn’t see time in a linear capacity, so his body isn’t reforming over a week, it’s reforming all at the same time with everything else occurring simultaneously. It’s like he views every moment in its own unique way, like every moment is its own crystal with a thousand thousand thousand thousand sides to it and every moment lined up one after the other puts things in a linear fashion, and that’s based on the human ability and capacity for understanding and interpreting time, concepts of time, and the manifestation of reality. Osterman’s transformation from human to whatever Dr. Manhattan is removes him from the fetters and chains of human perception; I think—and I can’t remember if this is maybe this is something the Watchmen tv series speaks on or not—it would be interesting to see what Manhattan’s view of himself is, because if time doesn’t matter, if so-called reality doesn’t matter, clearly physical form and presentation thereof can’t matter either, so gendered pronouns are probably incorrect to use with respect to the good doctor. So, if Dr. Manhattan sees the world in a way that is ontologically unique from humans, he can’t be a hero; he can’t be a superhero; what he can be is the most aware being on the planet and, by that same token, the loneliest, the most separate, the most alone. While John Donne astutely stated that “no man is an island entire of itself”, that notion can’t apply to Dr. Manhattan. The good doctor is not just an island unto himself, but a planet, a galaxy, an entire cosmos, if, in fact, our perception of those things can even apply to him.

I was just speaking with my partner about the good doctor and how he presented in the world, and the words of the peerless Bill Hicks—may he be free from rebirth—popped into my mind: “Today a young man on acid realized that all matter is merely energy condensed to a slow vibration, that we are all one consciousness experiencing itself subjectively, there is no such thing as death, life is only a dream, and we are the imagination of of ourselves.” If he didn’t have to cater to human perception, would Dr. Manhattan present as a ball of energy? Would he even present as anything, or would he exist on an energetic level imperceptible to human understanding of sense? I think that would be the case.

And, yet, what makes the doctor such a compelling and fascinating character is while physically and intellectually he is on another plane of existence, emotionally he doesn’t seem to have transcended anything. The cost of transformation was damn near everything for him, but he still feels the same way other humans do. When he says he is “tired of being caught in the tangle of their lives”, I don’t think he’s expressing his disdain for being a political and military and social mechanism, but, rather, he is trying to reconcile his very existence with the feelings he might perceive as being vestigial in nature. It must be painful for him to be able to recognize time as a human tool to gauge the gradual breakdown of life and matter, but be unable to totally disconnect from the emotions he possessed as John Osterman. In some ways, Dr. Manhattan is the most complex being in the world because of his abilities and understanding thereof, along with his possession of feeling emotion and sense attachment, but he masquerades as the simplest being because he can see every moving part as it exists; however, what precludes him from being the most complex entity in the world is his inability to separate himself from sensation, from attachment to outcome and impact. His move to Mars isn’t necessarily a choice of his, but rather a reaction to circumstance, to his old life, to things he thought he’d left behind and maybe had chosen to ignore. In the brilliant Magnolia, the similarly brilliant Paul Thomas Anderson says, '“we may be through with the past, but the past ain’t through with us.” Even when the good doctor leaves, everyone dwelling on earth is still wishing for and wondering about Dr. Manhattan. Where did he go? Is he gone for sure? Is he ever coming back? Moreover, can Dr. Manhattan actually be through with the past? With his own past? Is escaping to Mars anything but running from everything of which he is afraid? Does he escape to Mars because of his inability to navigate a reality within which he claims to see little value? What would he do on his red planet, in his palace of glass? Would he be content to be alone for eternity, or would he be forced to move again when the spectre of humanity once again encroached upon his reality? Is Dr. Manhattan actually capable of existing beyond the veil of maya, or is he just far enough along to be able to see the veil?

Wow, a lot about Dr. Manhattan, huh? You, Dear Reader, can tell I think a lot about him and his engagement with humanity. Maybe I took the easy way out here in looking at heroes and Watchmen by picking, arguably, the most compelling character in the book, or at least who I think is the most compelling. I also have deep attachment to Rorschach, too—“My face! Give it back!”, and “MY FACE! GIVE ME BACK MY FACE” are two of the most deeply rooted lines for me of any character in fiction, film, etc.—but his concepts of identity, at least to me, is much less nuanced than that of Manhattan’s, and closer in nature to Tom Stall in the film adaptation of A History of Violence. Just like how Tom says he killed Joey in the desert all those years ago, Rorschach’s birth persona, Walter Kovacs, died years earlier, too; or maybe, Rorschach killed Kovacs because there is only room for one personality in the human form. On that same token, I think a lot about Breaking Bad and how I believe Walter White to have died early on in the series, having been replaced by Heisenberg who masquerades as Walter White until the end.

A common thread I see with Dr. Manhattan, with Rorschach, Tom Stall, Walter White, etc. is everyone’s been forced into a total change of their identities without any choice in the matter. They’ve been forced to become someone else, and, surprise surprise, there are moments of absolute solitude and aloneness, whether that be on Mars, in the gutters, anywhere USA, or in the suburbs. All of these above mentioned characters stand alone and, in some cases, die alone. Maybe, just like 100 Demons say, “you’ll be dying in your own arms.”